Hail in Boulder, Colorado: Summertime hail could all but disappear from the eastern flank of Colorado's Rocky Mountains by 2070, according to a new modeling study by scientists from NOAA and several other institutions. (Credit: NOAA)

|

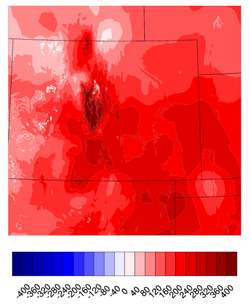

Freezing levels rise: This map of Colorado shows the difference between future (higher) and past (lower) freezing level heights captured in a new climate modeling study. Over Colorado's central Rocky Mountains, climate warming could push freezing level heights 400 m (1,300 feet) higher by 2070. (Credit: NOAA)

|

|

Contact: Kelly Mahoney

|

A future without hail?

Study suggests climate change may shift Colorado's Front Range hail to rain

January 9, 2012

On the lee side of Colorado's Rocky Mountains, hikers and homeowners know that summer afternoons often bring in noisy hailstorms. Usually, the hailstones are pea-sized or smaller and cause little damage. And, the hail may actually serve a useful purpose – by lowering flood risk.

"Hail takes awhile to melt, so it's thought that above about 7,500 feet in elevation, hail may lessen the risk of flooding," said Kelly Mahoney, Ph.D., a postdoctoral scientist working at NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratories, Physical Sciences Laboratory.

But decision-makers may not want to rely on hail's ability to lessen flood risk in the future, given climate change.

In a new modeling study published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change, Mahoney and her colleagues found that summertime hail could all but disappear from the eastern flank of Colorado's Rocky Mountains by 2070. Such a shift from hail to rain could mean more runoff, which could raise the risk of flash floods.

The researchers – from NOAA, the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) – focused on storms involving relatively small hailstones (up to pea-sized) on Colorado's Front Range, a region that stretches from the foothill communities of Colorado Springs, Denver and Fort Collins up to the Continental Divide. Decision-makers concerned about the safety of mountain dams and flood risk have been interested in how climate change may affect the amount and nature of precipitation in the region.

Mahoney and her study co-authors began exploring that question with results from two existing global climate models. Those models assumed that levels of climate-warming greenhouse gases will continue to increase in the future. But the weather processes that form hail – thunderstorm formation, for example – occur on much smaller scales than can be reproduced by global models.

So the team "downscaled" the global model results twice, first to regional-scale models that can take regional topography and other details into account (a step completed as part of NCAR's North American Regional Climate Change Assessment Program). Then, the regional results were further downscaled to weather-scale models that can simulate the details of individual storms and even the in-cloud processes that create hail.

Finally, the team compared the hailstorms of the future (2041-2070) to those of the past (1971-2000) as captured by the same sets of downscaled models.

Results were similar in experiments with both climate models, Mahoney said: "We found a near elimination of hail at the surface."

In the future, increasingly intense storms may actually produce more hail inside clouds, the team found. However, because those relatively small hailstones fall through a warmer atmosphere, they melt quickly and fall as rain at the surface – or evaporate back into the atmosphere.

"With climate change, we are examining potential changes in the magnitude and character of precipitation at high elevations," said John England, Ph.D., a flood hydrology specialist at the Bureau of Reclamation in Denver, Colo. "The Bureau of Reclamation will now take these scientific results and determine any implications for its facilities in the Front Range of Colorado."